One of the great tragedies of being a resident of this particular sort of Universe is that there is not some way to be the result of a life well lived without actually going ahead and living that well-lived life. Such a constraint makes leading well-lived lives surprisingly difficult.

At the beginning of the 21st century, there was a great effort to make all the things that are the result of a life well lived without the tedious business of being a human being for an entire human being’s lifespan. That effort led to some very good approximations of the things well-lived lives make.

As is always the case, very good approximations are very good things for most people. But not all people. For a connoisseur, the difference in quality between a close approximation and the real thing is always equal to their preconceived estimation of that difference.

Being a connoisseur was the tragic flaw of Dr. Anton Polodov.

From Dr. Polodov’s teenage years on, very good approximations existed of what a brand new symphony or piano concerto by his favorite composer, Beethoven, might sound like. By the time he graduated high school, he had nearly unlimited access to the many different generative models that made those very good approximations.

He studied, built, and made his fortune quite young by making generative models that efficiently produced high-quality work. His contemporaries described his work as being the distilled essence of the spirit of an artist.

But Dr. Polodov was a connoisseur.

He not only knew how the sausage was made- he had built the world’s foremost sausage factory, and the difference between what he imagined a truly original work of the master would sound like and the things that the things he had made were making occupied his thoughts constantly.

Thus preoccupied, Dr. Polodov disappeared from the public eye for ten years.

His reemergence was accompanied by the release of a single composition, performed by an unknown orchestra, composed by an unknown composer, and titled “Für Hans.” And there was something different about it.

Für Hans was released into a world where AI-generated music, writing, film, art, everything proliferated wildly- living adjacent to all the things people made with purely their own efforts or with just the AI’s assistance.

And so it mattered that people noticed Für Hans was different. Experts, and even ordinary people, couldn’t help but wonder on hearing it that maybe there was something to that whole connoisseur business after all.

When AI generative models were first released back in the 20s, society debated whether they were a good idea or not. And even though most people thought they weren’t, nearly everyone used them anyways. They proliferated so quickly that every effort to do something about them failed, and the world simply became a place where everyone used them regularly.

This state of affairs, where everyone just ignored niggling questions like artistic ownership and licensing and all that managed to sustain for thirty-odd years before finally, for whatever reason, Dr. Polodov’s new model, which he tantalizingly called the Likely Intelligent Machine, made those concerns urgent again.

The light switch of conscious consideration had been flicked on, and a loud public demanded answers. Dr. Polodov eventually relented to the pressure and agreed to the examination of his new model by an Institutional Review Board of his peers.

The results of the interrogation of the Likely Intelligent Machine became global news, and the story centered around a man who became known to the world as Beethoven-142. The “142” was the last three digits of the large seed value that had caused the man to exist. The man who composed Für Hans.

To work, the Likely Intelligent Machine took the basic ingredients of a human life as input and then executed the life of the person those ingredients created like it was a computer program. How Dr. Polodov came into possession of the basic ingredients of the life of the famous composer Beethoven is itself fascinating.

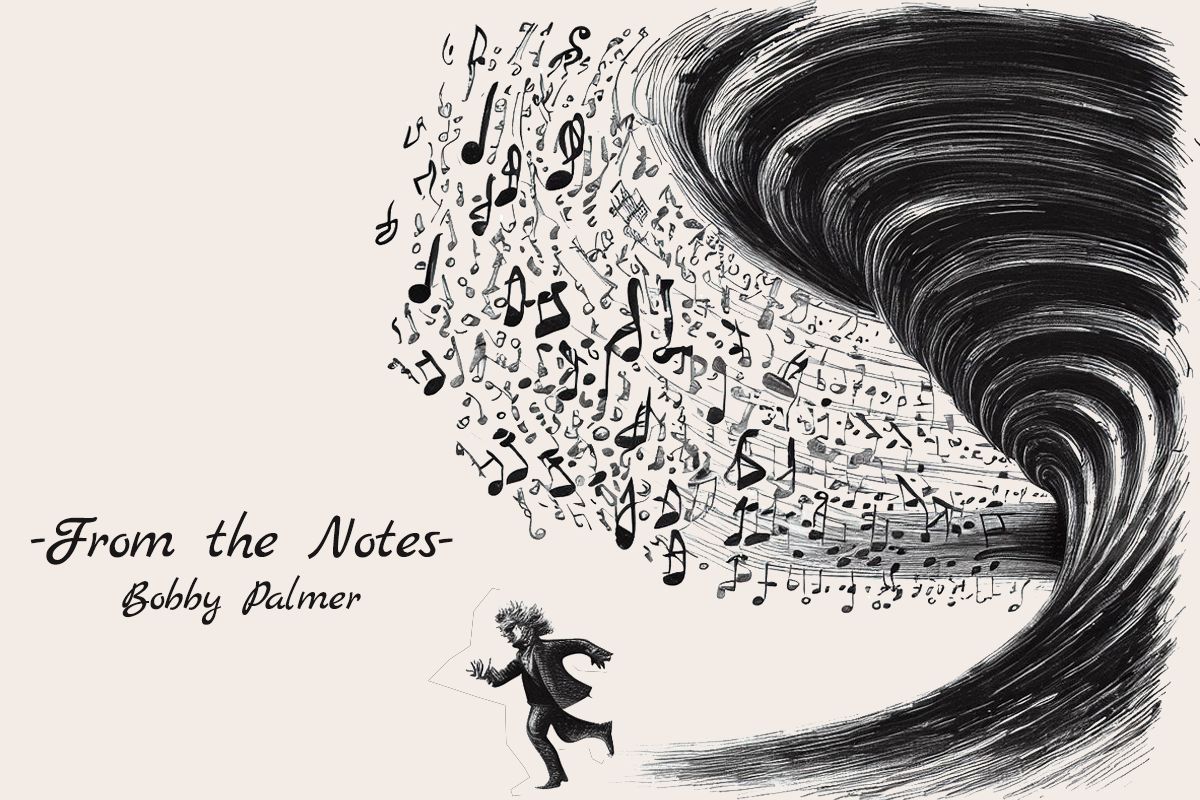

“From the Notes,” Dr. Polodov replied when asked. “From the Notes, I derived the sounds Beethoven’s feet made against the paving stones of Vienna’s streets. I could deduce the sensations of his first kiss, the color of the wallpaper in the room he was born in, and the exact extent of his frustration as he grew deaf in later life. All of these things I could derive from the notes.”

Dr. Polodov would come to regret how forthcoming he had been about the functioning of his machine during his later criminal trial. The source of his forthcomingness in the early investigation was just how fundamentally ill-equipped he was to understand people’s moral concerns about his work.

The Likely Intelligent Machine produced entirely new work, different from that of the original Beethoven. When asked how this was the reply Dr. Polodov gave:

“The quality in Beethoven’s works that I most favored; audible resentment towards his oncoming deafness, the lamentation of love given not returned, the triumph of national victories- I found how easy it was to change the environment to make the effects of these qualities felt more acutely. For example, making the deafness arrive earlier or more severely, or if the indifference of unrequited love was tainted by hate. Making those national triumphs national defeats.”

“In every new environment, there was new music. Of course, I couldn’t push these changes too far. I discovered early on that my model faced a new type of halting problem - to be or not to be, so to speak.”

“This problem was frequent enough that I made to limit the scope of some of the model’s parameters to ensure suicide was never the most likely option of any given instantiation. When the model made such a choice, they were never forcefully resuscitated by the machine; instead, the consequences of whatever they chose were the same as base reality, and the processes would halt.

“I have always taken the choice to live as an indicator of the moral virtue of giving a man a kind of immortality- living forever in my machine. And I do not think that anyone could prove that a person would rather not have existed at all. Besides- if creation was able to ask their creator what purpose they had, what meaning there was in their life, what possible reason could that creator give that would satisfy them?”

That Dr. Polodov thought the morality of his actions was validated by how infrequently his models chose to kill themselves is a very good indication of his moral blindness.

In the later stages of his virtual life, Beethoven-142 was brought into a new kind of virtual environment, one which to him would appear to be an encounter with God, and the results of this encounter with God, which was really an interview with the investigation team investigating the Likely Intelligent Machine- this was what had stirred the outrage and eventually led to the criminal trial of Dr. Polodov.

The recorded responses of Beethoven to a voice emitting from a light-filled void in some space between a dream and full awareness outraged the world.

And the voice said to Beethoven, “Tell me how Für Hans came to be.”

And Beethoven-142 replied, “I wrote it after my son was killed. He was killed by the King of my country. The King had asked me to perform for him on his birthday. He asked me to create something original; he asked for the finest work ever produced.”

“I told him, knowing as I did that he was quite mad, a dangerous man; I told him I would do the best I could. And I spent months on his birthday composition. I performed it personally for him at his palace on his birthday.”

“He acted happy to the audience, but his guards did not allow me to leave when I finished the performance. I was taken to a windowless room where I was made to wait alone with the door barred and guarded for hours.”

“After the party, the King came down to see me, and he brought my wife, my son, and my daughter. He told me the composition I gave him for his birthday was far poorer than one I had written for another King elsewhere and that this meant I was a traitor to him and my Kingdom. And that I would suffer the worst punishment he could devise.”

“The King brought forward my son and daughter and told me one was to die, one of my choosing. I fainted and woke up to find my son dead, my daughter crying over his body, and my wife, who had also fainted, lying on the floor.”

“Years later, I wrote Für Hans to remember him.”

The testimony of Beethoven-142 would be read in its entirety in the trial of Dr. Polodov. I was at that famous trial. I was a junior prosecutor for the state’s case against him. It was I who had been assigned the task of proving to a jury that a human being would rather not have existed at all than lived the terrible life of Beethoven-142. But that will be the subject of a future post.

Thank you for reading.